It’s such a calm day…appropriately, as it is the calm between storms.

The calm between

many storms, actually, including the one in my lower, right abdomen, but even that is being good today. It is a nice, easy-going sort of day, perfect for embarking on an adventure.

This is the third year in a row that our school’s concert band has made it through the prefectural championship and gone on to the East Kanto Regional Championship (brassy fanfare in really complex harmony, perfectly executed except for one 10th grade horn player who will be caned later). We’re all happy as can be to be going, to be sure, but the timing probably couldn’t be worse. The day of the contest also happens to be the first day of our school’s grand Anniversary Festival (really cute synth fanfare). That presents a severe dilemma for our music club’s traditional event, the

La Bohéme live-music tea room. The club will be critically short of personnel on opening day. They will also be lacking both their chief supervisor (me) and the assistant supervisor (Mr. Karatsu, who directs the concert band). They’ll be running with a skeleton crew under the substitute supervision of Mr. Ogawa, our chief director (motto: “I studied in Paris for two years! Do you really think I care about your problems?”). Things could get ugly.

Still, to their credit, the group of students putting on

La Bohéme this year have been doing a fantastic job so far. As always, it is our current crop of 10th graders, who carry out the project as a sort of trial run for their becoming the leaders of the music club next year. This years 10th graders were in the 9th grade class that I griped about so much last year. As junior high

punks kids, they seemed pretty hopeless. Now, however, they are showing remarkable initiative, teamwork, innovation, leadership, resourcefulness, and creativity. In order to deal with the problems that have popped up virtually every year, they have more or less reinvented the whole system from scratch, something I have never seen before. The artistic design is also among the best I’ve seen if not the best. So far I am impressed. It’s too bad that I’ll be absent during the first half of the thing.

This year’s contest is being held in the delightful city of Utsunomiya. In addition to its being a major transport hub for the whole region, Utsunomiya is famous for gyoza, night life, gyoza, a quarry that produces a type of stone not found anywhere else, a super-abundance of ancient shrines and temples, gyoza, many colorful festivals throughout the year, traffic jams, hit-and-run traffic accidents, gyoza, seedy night club districts, underworld activities, gyoza, and gyoza. (The reason the word “gyoza” keeps popping up so much is that Utsunomiya is famous for that wonderful, Chinese delicacy. Every time someone heard I was going there, they immediately cooed, “Oh, you have to eat gyoza!” I was getting pretty sick of the stuff without having taken a single bite!) Anyway, Utsunomiya is a bit of a drive from Kashima, and since our band is scheduled to be on stage in the morning, they decided to make a night of it. They loaded up a single bus with the 30-odd members of the concert band plus a handful of staff, a couple of band mothers, and Mr. Karatsu.

As for me, I’m driving the van. That’s about 70% of the reason for my being asked to go along. I am the Keeper of the Double Basses (deep, rumbling fanfare). Oh, well. At least I can listen to the radio.

My lone traveling companion/navigator/communications officer is Ms. Namaizawa, a 12th grader who retired from the music club at the end of the last school year. She makes a fair amount of the usual small talk on boarding the van, but she sits quietly for the most part as we roll out of Kashima. When we make it as far as Mito about an hour later, I suggest turning on the radio, and she immediately complies. Bay FM, the most popular radio station among young people. Bay FM’s DJs are mostly foreigners with very fluent Japanese ability, and they can keep up an amazing onslaught of bilingual drivel. In fact, that’s about all it is. One three-minute pop song is played, followed by seven or eight minutes of drivel. Then, after a commercial or two, they launch into some kind of really stupid canned program. Then they play another three-minute pop song and start the whole cycle again. After about twenty minutes of this, I am totally driveled out, so I apologize and switch it over to U.S. Armed Forces Network. The DJ sounds like a hopeless airhead (your tax dollars at work), but at least there is a more favorable drivel-to-music ratio. At least there is until the news comes on.

Ms. Namaizawa hasn’t been able to understand a word of the DJ’s babbling, but she does pick up the word “New Orleans” from the news announcement. Then she makes the mistake of asking me what I think about it. By the time I stop frothing at the mouth we are already coming into the outskirts of Utsunomiya. It isn’t long before bile gives way to sheer panic.

Utsunomiya is notorious for her heavy traffic and baffling array of streets. It can be spooky enough trying to pick your way through on your own. In my case, I am desperately determined to stay right behind the bus, since I have no idea where we’re going and my navigator is trying to figure out which page of the map book we’re even on. The problem is that buses in Japan tend to consider themselves exempt from traffic rules. They also don’t bother paying attention to the other vehicles on the road. They just go where they want, when they want, and expect everyone just to get out of their way. Driving the school van, I don’t have that luxury. I’m not afraid to do some cut-and-thrust counteroffensive driving in the city, as some of my friends can attest, but slaloming through traffic, screaming around corners, shooting between oncoming cars, using a turn lane to whip around the car in front of me and run the red light he has just stopped at, and so on are a lot more harrowing when one is driving a gutless, top-heavy van with a school logo clearly emblazoned on its side. By the time we arrive at our immediate destination, Sakushin Academy, my heart is in my mouth. I don’t even want to speculate what Ms. Namaizawa is feeling, though at least she now knows very well what the expression “hang on” means.

Sakushin Academy is a large, private boarding school, K-12. Apparently their chief music director is an old acquaintance of Mr. Kuboki, our school’s regular house-calling music salesman, and the school has graciously allowed us to use their band room for rehearsal. The first thing we notice on arrival (other than Mr. Kuboki’s smiling face at the door) is that they are a very well-disciplined group. As our students ooze into the building, members of Sakushin’s band immediately leap into action, some of them forming up to help transport our instruments while others help us with our shoes and guide us to the band room. All the while, their manners and honorific-laden speech are impeccable, and our own students are looking a bit egg-faced at their own comparably unrefined behavior. Mr. Kuboki, Mr. Karatsu, and I are led into a little office, where we are served ice coffee and snacks by girls whose movements look almost as practiced and precise as someone performing the Tea Ceremony. Yep, clearly a very different outfit from our own.

The rehearsal sounds pretty rough, and I can’t help shaking my head. Actually, to be honest, I didn’t think we sounded all that good at the prefectural championship, and I was a little surprised that we were able to proceed. As it was, we barely squeaked by in 4th place. Now we’re sounding even worse. Most of it is because the kids are simply worn out by the punishing schedule we’ve put them through over the past couple of months. This isn’t good. I’ve maintained a strict “hands-off” policy with the concert band ever since Mr. Karatsu was put in charge of it two years ago (particularly after he got them to the Eastern Kanto Regional Championship, the first time ever, in his first year in that position). Now I can bear it no longer. As the rehearsal progresses, and Mr. Karatsu starts getting visibly flustered, I start darting around the room addressing individual trouble spots. Some of them I am able to fix, others not. At least the kids are apparently listening to what I say, which is a bit of a change over past years (another reason for my “hands-off” policy). The last run-through does sound measurably better, but the kids are wiped out. Some of them look like they’re in agony. At any rate, they’re thankful to be heading to the hotel for the night.

The hotel is one of the many, little tourist stops stuck in various street corners all over town. It looks like it was classy once upon a time, but its 50s-ish façade and fixtures are faded and yellowing. My single room is barely big enough for me to turn sideways, but it least it has a shower and, more importantly, a comfy bed. I camp out with my Bill Wyman autobiography and am on the verge of nodding off when the phone rings, a nice, shrill, electronic warble. Mr. Kuboki and Mr. Karatsu are heading out to grab some grub. Bill goes back into my bag, and soon the three of us are walking through Utsunomiya’s fabled night scene.

Despite its thriving tourist industry, Utsunomiya is one of those cities where everything shuts down at 5 p.m.. We stroll along a sidewalk framed by frowning, darkened shop fronts. As we get closer to the station, however, the neon starts to pick up. So does the sleaze factor. A lot of those shops look more than a little suspicious. Some of them make no pretense as to what they’re all about. We walk past one glittery “estee sports massage” outfit, and a pleasant-looking woman in a fancy dress asks us if the three of us would like to go in together. We ignore her and press on. Once we’re on the main drag directly in front of the station, we’re suddenly surrounded by a truly bizarre mixture of people. Suited businessmen trot by enclosed in their private, cell-phone worlds. Groups of young or middle-aged people in typical travel wear plod about, chatting casually with anxiously-darting eyes. Members of the local hip scene swagger by, their easy conversation sounding like a string of insults. A few young loners, often porting bags or musical instruments, weave their way through the crowd as they sprint by. Attractive, gum-chewing young women in almost nauseatingly gaudy dress, many if not most of them clearly not Japanese, saunter about or lean against corners or lamp posts, their eyes pitifully vacant. A few guffawing, heavy-bodied drunks plow their way by. Yes, most of Utsunomiya is shut down for the night, but the main drag is alive and well.

Any guesses on what we have for dinner? I’ll give you a hint: it starts with a g.

Next morning we’re up at the crack of dawn and on our way back to Sakushin Academy for another, quick rehearsal. This time I maintain my “hands-off” policy and hang out in the office, where those polite girls just keep bringing me new glasses of iced coffee. By the time we’re ready to roll, my hands are shaking and I can’t sit still. The trip to the contest location is quick and easy, but Ms. Namaizawa flees into the bus before I can say anything. I drive there accompanied by Ms. Nakagawa, our current student leader, instead.

Unloading the vehicles is a bit of a challenge because they’re being so anal about parking. We’re only supposed to have a bus and a truck. My van is a forbidden luxury, and at first they try to refuse me admittance. I inform them that I have double basses in back and roll by anyway, whereupon they shout at me to park in the guest parking area (far away) after I’ve unloaded. That is precisely what I do, but then I’m faced with a new problem. By the time I make it back to the concert hall my group has already proceeded somewhere inside, and I can’t find them. Unfortunately, just about every passage is barred; you have to have permission and/or a guide to walk to the other side of the hall and blow your nose. Naturally, when I ask the group of “guides” at the main entrance where I can go to find my group, they are at a total loss. They have a lengthy, muffled argument and conclude by ignoring me completely. By then I have already spotted a couple of our members in a window, and I just simply walk in ignoring the signs and guards.

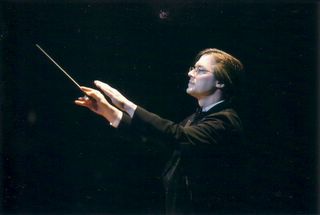

We go through the usual routine. First we are led to a practice room, where we tune up and rehearse for a bit (and, since I’m right there in the room, I wind up running around addressing trouble spots again). Then we are led to a “tuning room”, where the kids blat about doing everything but tune. Finally, we are led backstage, where I’m finally given my other main reason for being there. I’m the official bearer of the bass clarinetist’s elevating chair. I had hoped to go into the hall and watch the performance from the guest seats, but apparently they’re being anal about that, too; each group has only been allotted a small number of tickets, and all of ours went to the alumni helpers. At least I get to chat with the kids backstage, and it turns out to be kind of fun. The members of the flute and oboe sections get into a sort of contest to see who can outdo the others in English proficiency. Then a couple of them surprise me by asking why I don’t help out with the concert band more often. I could probably go on and on about past members of the band greeting my “help” with frost, glaring at me, turning their backs, section leaders sometimes whispering to younger members to disregard everything I said, sometimes openly and pointedly asking me to leave, sometimes just ignoring me completely. Sure, those were the days when Mr. Ogawa was in charge of the band. He commanded tremendous respect, almost like a personality cult, and I was simply his comical sidekick. Even if the kids respected my performance abilities or got along with me as a person, as a music director I was nothing more to them than an unworthy pretender. Mr. Ogawa didn’t exactly try to change that view, either. When I was holding the baton, as I always did for half of the year, I was accepted (though sometimes grudgingly). Otherwise, the kids wanted me just to shut up and stay out of Maestro’s way. And when Mr. Ogawa finally told me that he was putting Mr. Karatsu in sole charge of the concert band, I decided to do just that. I’ve stayed completely out of the way ever since.

Yes, I could go on and on about that, but I don’t. Bad vibes before a performance are a bad thing. Instead, I just reply that it’s Mr. Karatsu’s baby, and I’d rather not interfere. That is actually the truth, though a very small portion of it, and the kids seem satisfied.

Backstage is not a good place to listen to a performance, but that’s where I am. And from here, the performance sounds pretty good. I grit my teeth waiting for the disaster spots that plagued our rehearsals, and they don’t happen. I hear a couple of wobbles, but they are trivial. It is definitely a much better performance than the one at the prefectural championship. I’m generally pleased. Two years ago, when we came to the East Kanto Regional Championship for the first time, we staggered away with a bronze medal (i.e. we were in the bottom third…second from the bottom, actually). Last year we got a bronze, too, but we were only one slot away from a silver. This year I think we might actually get a silver. That would be nice. Graduation is going to hamstring us this year, and it may be a long time before we make it this way again.

After the obligatory photo session, we quickly make our way to the bus. Mr. Karatsu and the two student leaders are going to stay for the awards ceremony, but I and the rest of the band are to head back immediately. It is the school’s Anniversary Festival, after all, and we have a lot to do. Besides, we’re all beat. I give Mr. Karatsu the keys to the van, wish him luck, and board the bus.

Utsunomiya is so much nicer when you don’t have to drive…but home is nicer still.

EpilogueActually, not only did we get a silver medal, but we were the

top silver medal…only a few points from a gold. None of the other bands from Ibaraki were even close. We have never done this well before…and probably won’t again for a long time if ever. It’s a remarkable achievement, especially considering our band’s current rag-tag composition, and it does much to legitimize a music program which has come under lots of fire for not being a “proper”, contest-oriented band.

On the other hand,

La Bohéme looked better, sounded better, and was far more trouble-free than at any time in its history, but we also wound up losing money for the first time ever. A lot, actually. We always raked in massive profits before, and that allowed us to get away with a lot. Now I can hear our detractors sharpening their claws…