Music in the Mountains, Part 2007 ch. III

"Okay, girls, come in."

The clinician then emerges from the foyer into the living room of the suite where the male teachers are all quartered. Seeing me there, he levels those famously (and very deceptively) gentle-looking eyes on me and says, "Ah! You don't mind, do you? I'm giving the girls in my section some extra training."

I grin. "That's okay."

He smiles in return and then calls back in the direction of the foyer. The girls emerge. There are three of them, grades 11, 9, and 7, and naturally their chosen instrument is the same as the clinician's. (I won't say which just in case one of the spies might make a stink about "privacy".) However, they don't have their instruments with them. All they have are shy smiles.

The clinician strikes an authoritarian pose. "Okay," he says, "first of all, we'll have some social training." He gestures around the room, which still bears the scars (read "garbage and dirty dishes") of last night's welcome party. "Clean it up! All of it!"

"Hai," say the girls, bowing in perfect unison, and they snap into action.

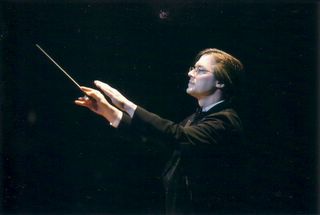

This clinician is one of our regulars. He not only comes to our summer training camp almost every year, but he often visits Ye Olde Academy. He's a well-established and very capable player of a very difficult instrument. He's also a very good teacher. Despite his gentle-looking face and the soft, sensitive way he plays his instrument, the man can be a serious hard-ass. Not one to suffer any loose ends, he can seem downright tyrannical at times. He's also eccentric as they come. But the man can teach. Yes, the man can be a damned good teacher.

Not that he rests on his laurels. When the girls set to work cleaning up, the clinician gets right in and works with them, giving them instruction all the way. At one point I even hear him in the kitchen telling one girl a better way to hold a wine glass while washing it so as to minimize the chance of dropping and breaking it. He's definitely one for detail.

The girls are efficient, and the "social education" doesn't last long. Next the clinician calls the girls into the living room and asks them to sit in a half circle in front of him.

"Now it's time for some cultural education," he says. Then, throwing a glance at me, he adds, "and I think you may be interested in this, too."

He reaches into his nearby pile of luggage and pulls out a long, thin object wrapped in cloth. When he arrived, he told us all that it was a Japanese sword. We assumed he was joking. He wasn't. Assuming a traditional, seiza-style sitting position (i.e. sitting on his heels), he removes the cloth cover. Then he calls the girls to attention, performs a sort of ritual, unlocks the sword, and removes it from its sheath.

The three girls' mouths drop open in perfect sync. Mine is half a beat late.

The sword is beautiful. Though it's in excellent condition, it definitely looks old. It is clear that, to the clinician, it is a great treasure.

"This sword dates from the Muromachi Era (1336 to 1573)," he says with both pride and admiration. My eyes narrow; that seems a bit hard to believe. (I also have to wonder why he even has such a sword, though his surname is a famous samurai one. It may very well be a family heirloom.) Grinning shallowly, he holds up a piece of heavy paper and, with a casual motion, shreds it. The blade is razor sharp. The clinician then goes on to point out various features of the sword's construction. Whether the weapon is genuine or not, the craftsmanship is truly amazing. The clinician describes the process used to craft the blade and also explains exactly why it is shaped the way it is. It's not for decoration. It also makes me wonder about one very obvious nick, more like an irregular groove, on the parrying edge. Did that blade see action?

He definitely has the girls' attention.

"This is a serious weapon," he goes on, "and it can be quite dangerous. Never point the blade at someone unless you mean it, and always hand it to someone pommel first, blade flat." He then demonstrates by handing it to me. "Go on, [Moody], give it a try!"

Genuine or not, the sword is very well balanced. I step well away from the others and give it a couple of careful swings. It's much heavier than I expected, but it almost seems to move itself. The grip and the swing feel very natural.

Taking the sword back from me (pommel first, blade flat), the clinician says, "To a samurai, this isn't just a weapon, it's a way of life. It's a part of him, so he treats it even better than he would part of his own body." He opens a little kit and takes out a bottle of oil and some tools. "It also takes lots of special care." He puts some oil on an odd-looking, little brush and begins dabbing it on the blade. "Treat it well, and it will treat you well...for a long time. I mean, look at this! It was made hundreds of years ago, and it's still alive!" He finishes oiling the blade, puts the kit away, and goes on, "You see, there's more to swordsmanship than just slashing and thrusting. You have to get to know your sword. You have to make it part of you. It has to work through you, and you through it. You have to respect it, you have to love it, and you have to take care of it!"

The three girls are enthralled. So am I.

The clinician sheaths the blade, performs the ritual again, and restores the cloth cover.

"Do I make myself clear?" he asks, eyeing us intently.

"Hai," say the three girls, still entranced. I nod briskly.

"Now...," he says very deliberately, "what about your instrument? Do you know it and treat it the same way?"

The girls look at each other and flash Japanese smiles of embarrassment. Then they emit unison hums of uncertainty.

"Think about it," says the clinician. Then he changes the topic to some more obvious ones regarding samurai culture and how it compares to the modern day. It's an interesting discussion, and it's unfortunate when the girls have to leave to go to their next rehearsal session.

Once the girls have gone, the clinician shrugs, sighs, and asks, "So, do you think they got it?"

"I'm sure they'll at least be thinking and talking about it for some time," I reply. "Besides, I really enjoyed it!"

"Good enough, then," he retorts, and with a shallow bow he heads for the exit himself.

Never a dull moment at these summer camps, even when it tries really hard.

The clinician then emerges from the foyer into the living room of the suite where the male teachers are all quartered. Seeing me there, he levels those famously (and very deceptively) gentle-looking eyes on me and says, "Ah! You don't mind, do you? I'm giving the girls in my section some extra training."

I grin. "That's okay."

He smiles in return and then calls back in the direction of the foyer. The girls emerge. There are three of them, grades 11, 9, and 7, and naturally their chosen instrument is the same as the clinician's. (I won't say which just in case one of the spies might make a stink about "privacy".) However, they don't have their instruments with them. All they have are shy smiles.

The clinician strikes an authoritarian pose. "Okay," he says, "first of all, we'll have some social training." He gestures around the room, which still bears the scars (read "garbage and dirty dishes") of last night's welcome party. "Clean it up! All of it!"

"Hai," say the girls, bowing in perfect unison, and they snap into action.

This clinician is one of our regulars. He not only comes to our summer training camp almost every year, but he often visits Ye Olde Academy. He's a well-established and very capable player of a very difficult instrument. He's also a very good teacher. Despite his gentle-looking face and the soft, sensitive way he plays his instrument, the man can be a serious hard-ass. Not one to suffer any loose ends, he can seem downright tyrannical at times. He's also eccentric as they come. But the man can teach. Yes, the man can be a damned good teacher.

Not that he rests on his laurels. When the girls set to work cleaning up, the clinician gets right in and works with them, giving them instruction all the way. At one point I even hear him in the kitchen telling one girl a better way to hold a wine glass while washing it so as to minimize the chance of dropping and breaking it. He's definitely one for detail.

The girls are efficient, and the "social education" doesn't last long. Next the clinician calls the girls into the living room and asks them to sit in a half circle in front of him.

"Now it's time for some cultural education," he says. Then, throwing a glance at me, he adds, "and I think you may be interested in this, too."

He reaches into his nearby pile of luggage and pulls out a long, thin object wrapped in cloth. When he arrived, he told us all that it was a Japanese sword. We assumed he was joking. He wasn't. Assuming a traditional, seiza-style sitting position (i.e. sitting on his heels), he removes the cloth cover. Then he calls the girls to attention, performs a sort of ritual, unlocks the sword, and removes it from its sheath.

The three girls' mouths drop open in perfect sync. Mine is half a beat late.

The sword is beautiful. Though it's in excellent condition, it definitely looks old. It is clear that, to the clinician, it is a great treasure.

"This sword dates from the Muromachi Era (1336 to 1573)," he says with both pride and admiration. My eyes narrow; that seems a bit hard to believe. (I also have to wonder why he even has such a sword, though his surname is a famous samurai one. It may very well be a family heirloom.) Grinning shallowly, he holds up a piece of heavy paper and, with a casual motion, shreds it. The blade is razor sharp. The clinician then goes on to point out various features of the sword's construction. Whether the weapon is genuine or not, the craftsmanship is truly amazing. The clinician describes the process used to craft the blade and also explains exactly why it is shaped the way it is. It's not for decoration. It also makes me wonder about one very obvious nick, more like an irregular groove, on the parrying edge. Did that blade see action?

He definitely has the girls' attention.

"This is a serious weapon," he goes on, "and it can be quite dangerous. Never point the blade at someone unless you mean it, and always hand it to someone pommel first, blade flat." He then demonstrates by handing it to me. "Go on, [Moody], give it a try!"

Genuine or not, the sword is very well balanced. I step well away from the others and give it a couple of careful swings. It's much heavier than I expected, but it almost seems to move itself. The grip and the swing feel very natural.

Taking the sword back from me (pommel first, blade flat), the clinician says, "To a samurai, this isn't just a weapon, it's a way of life. It's a part of him, so he treats it even better than he would part of his own body." He opens a little kit and takes out a bottle of oil and some tools. "It also takes lots of special care." He puts some oil on an odd-looking, little brush and begins dabbing it on the blade. "Treat it well, and it will treat you well...for a long time. I mean, look at this! It was made hundreds of years ago, and it's still alive!" He finishes oiling the blade, puts the kit away, and goes on, "You see, there's more to swordsmanship than just slashing and thrusting. You have to get to know your sword. You have to make it part of you. It has to work through you, and you through it. You have to respect it, you have to love it, and you have to take care of it!"

The three girls are enthralled. So am I.

The clinician sheaths the blade, performs the ritual again, and restores the cloth cover.

"Do I make myself clear?" he asks, eyeing us intently.

"Hai," say the three girls, still entranced. I nod briskly.

"Now...," he says very deliberately, "what about your instrument? Do you know it and treat it the same way?"

The girls look at each other and flash Japanese smiles of embarrassment. Then they emit unison hums of uncertainty.

"Think about it," says the clinician. Then he changes the topic to some more obvious ones regarding samurai culture and how it compares to the modern day. It's an interesting discussion, and it's unfortunate when the girls have to leave to go to their next rehearsal session.

Once the girls have gone, the clinician shrugs, sighs, and asks, "So, do you think they got it?"

"I'm sure they'll at least be thinking and talking about it for some time," I reply. "Besides, I really enjoyed it!"

"Good enough, then," he retorts, and with a shallow bow he heads for the exit himself.

Never a dull moment at these summer camps, even when it tries really hard.

8 Comments:

Wow,fascinating, fascinating...

What a way to get a point across.

And only in Japan.

By Olivia, at 12:40 AM

Olivia, at 12:40 AM

ooh spot the pun?

By Olivia, at 12:41 AM

Olivia, at 12:41 AM

You seem to be good at those, m'lady!

By The Moody Minstrel, at 1:39 AM

The Moody Minstrel, at 1:39 AM

"I'd rattle off a scabbard of puns too, but I am not that sharp," he scythed.

By Don Snabulus, at 5:22 AM

Don Snabulus, at 5:22 AM

So this is what is meant by working on your chops?

By Anonymous, at 10:45 AM

Anonymous, at 10:45 AM

Ba-dum BUM

By Anonymous, at 3:22 PM

Anonymous, at 3:22 PM

Now that is a camp moment and a very impressive teaching analogy.

By Swinebread, at 1:40 AM

Swinebread, at 1:40 AM

From Tom Swift: "This is not the time to split hairs", Tom said edgily.

What an excellent and apropos lesson. Just reading about it makes me want to be a Samurai of the trombone. He's very good. Don't go bringing any weapons to school though, Moody.

By Pandabonium, at 11:21 PM

Pandabonium, at 11:21 PM

Post a Comment

<< Home