Listening but Not Seeing, pt. II

It was back in February when I first heard that volunteer performers from the Kashima Philharmonic (current motto: "We're still not sure whether we suck or not, but we're trying") were going to be helping out with some sort of art exhibit. At the time I was asked to participate, and I gladly accepted. Then, about a month later, I asked for details and was told unceremoniously that the bill was full, and my services weren't needed after all. I figured that was that and went on with life.

In April I was once again asked to help, but in a totally different capacity. Mr. Ogawa told me that the artist to be featured at the exhibit had written a poem for every one of his works, and that some of them had been put to music. To be specific, there was a collection of tunes, each written by a different composer but still using the artist's poems as lyrics, compiled into a single work for a choir with a piano accompaniment. Someone involved with the upcoming exhibit had requested the Kashima Philharmonic put together a chamber orchestra and perform some of those tunes. Naturally, that meant someone had to arrange them for a chamber orchestra. Naturally, that someone was me.

The tunes were all, well, very typical examples of modern choral music, i.e. lots of bizarre time shifts and very close, often dissonant harmony. It wasn't a simple matter of transcribing the parts as they were; I had to put a lot of thought into it while still staying as close to the originals as possible. As usual, I got totally wrapped up in the project. Paying little heed to such trivial things as my job, I immersed myself in the tunes, tried to get to know them as best I could, even make them a part of myself, and then try to shape them into something of my own.

Looking at the book and the examples of the artist's work it contained, I had a fleeting feeling of familiarity (or was that "a familiar feeling of fleet..." never mind). It seemed I had seen that artist's work before, or at least something very much like it. I didn't pay it much mind, however, for I soon became too engrossed in the music to care.

In the end, however, the arranging didn't take me long at all. There were a little under a dozen tunes in the collection, and I had all of them but one scored and on Mr. Ogawa's desk within two weeks. (Mssr. Maestro was quite astonished, I can tell you!) I never heard anything more about it, though, so I figured the project had quietly dried up.

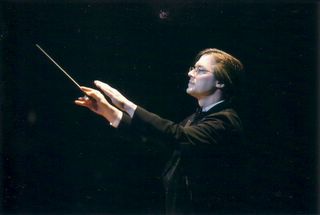

I'd figured wrong. At the end of the Kashima Philharmonic rehearsal on May 12th I was told that the chamber orchestra was going to try reading through my arrangements, which the members had apparently been practicing individually during the previous week (and which I had virtually forgotten). I was asked if I could hang around and make sure nothing needed fixing. Well, with all the bizarre tone palettes and changing meters (not to mention some very unorthodox musicality), we quickly found something that needed to be fixed: the lack of a conductor. I directed the rehearsal, and after selecting the pieces that would be used at the performance, the konzertmeisterin asked me if I could conduct them regularly. I agreed with some reservations knowing full well it was just another load to try to give time I really didn't have.

There were two performances, the first of which was on Saturday the 24th after my morning of guiding people (and ill-tempered old farts) to the mass choir rehearsal. Real communication was at a premium, and the schedule kept being subject to random changes, but I still managed to get myself over to the Kashima Workers' Culture Hall for the final rehearsal followed by the performance itself. It seemed like a comedy of errors. At least a fifth of the group had never rehearsed the pieces. We started the practice session with a couple of missing members, who came waltzing in (quite out of step with our changing meters) in the middle. And if rehearsal was a confusing joke, the Saturday performance was even worse. We were called to standby backstage only to find that the stage crew had no idea who was doing what where or when. It came down to a, "Well, why don't you let [so and so] go on first, and then we won't have to move the piano," sort of thing. The members of the chamber orchestra went onstage, but no one bothered to set up my director's stand, so I brought it out myself...and was immediately introduced by the announcer as the prelude to our performance, i.e. no time to tune up. The tuning was iffy. The execution was stilted. The conducting was awkward. The playing was tentative. The performance was lackluster. The crowd response was muted. The members of the orchestra were disappointed. The Moody Minstrel was out of the building and in his BLUE RAV4 headed homeward as soon as he could get out of there.

At least we had another chance to redeem ourselves on Sunday the 25th. Things got off to an awful start (i.e. no one told me our performance had been rescheduled half an hour earlier, so I showed up late...forcing them to reschedule it again). However, this time the stage was set up properly and the orchestra was able to tune up. I felt much more in the groove with my conducting, and the players responded well. It was a much better performance than Saturday's had been, and the audience response reflected it. We all felt much better afterward.

(When we had returned backstage one of the violinists said, "Now I finally understand these tunes! Can we perform them again?)

Translation:

Translation:

In April I was once again asked to help, but in a totally different capacity. Mr. Ogawa told me that the artist to be featured at the exhibit had written a poem for every one of his works, and that some of them had been put to music. To be specific, there was a collection of tunes, each written by a different composer but still using the artist's poems as lyrics, compiled into a single work for a choir with a piano accompaniment. Someone involved with the upcoming exhibit had requested the Kashima Philharmonic put together a chamber orchestra and perform some of those tunes. Naturally, that meant someone had to arrange them for a chamber orchestra. Naturally, that someone was me.

The tunes were all, well, very typical examples of modern choral music, i.e. lots of bizarre time shifts and very close, often dissonant harmony. It wasn't a simple matter of transcribing the parts as they were; I had to put a lot of thought into it while still staying as close to the originals as possible. As usual, I got totally wrapped up in the project. Paying little heed to such trivial things as my job, I immersed myself in the tunes, tried to get to know them as best I could, even make them a part of myself, and then try to shape them into something of my own.

Looking at the book and the examples of the artist's work it contained, I had a fleeting feeling of familiarity (or was that "a familiar feeling of fleet..." never mind). It seemed I had seen that artist's work before, or at least something very much like it. I didn't pay it much mind, however, for I soon became too engrossed in the music to care.

In the end, however, the arranging didn't take me long at all. There were a little under a dozen tunes in the collection, and I had all of them but one scored and on Mr. Ogawa's desk within two weeks. (Mssr. Maestro was quite astonished, I can tell you!) I never heard anything more about it, though, so I figured the project had quietly dried up.

I'd figured wrong. At the end of the Kashima Philharmonic rehearsal on May 12th I was told that the chamber orchestra was going to try reading through my arrangements, which the members had apparently been practicing individually during the previous week (and which I had virtually forgotten). I was asked if I could hang around and make sure nothing needed fixing. Well, with all the bizarre tone palettes and changing meters (not to mention some very unorthodox musicality), we quickly found something that needed to be fixed: the lack of a conductor. I directed the rehearsal, and after selecting the pieces that would be used at the performance, the konzertmeisterin asked me if I could conduct them regularly. I agreed with some reservations knowing full well it was just another load to try to give time I really didn't have.

There were two performances, the first of which was on Saturday the 24th after my morning of guiding people (and ill-tempered old farts) to the mass choir rehearsal. Real communication was at a premium, and the schedule kept being subject to random changes, but I still managed to get myself over to the Kashima Workers' Culture Hall for the final rehearsal followed by the performance itself. It seemed like a comedy of errors. At least a fifth of the group had never rehearsed the pieces. We started the practice session with a couple of missing members, who came waltzing in (quite out of step with our changing meters) in the middle. And if rehearsal was a confusing joke, the Saturday performance was even worse. We were called to standby backstage only to find that the stage crew had no idea who was doing what where or when. It came down to a, "Well, why don't you let [so and so] go on first, and then we won't have to move the piano," sort of thing. The members of the chamber orchestra went onstage, but no one bothered to set up my director's stand, so I brought it out myself...and was immediately introduced by the announcer as the prelude to our performance, i.e. no time to tune up. The tuning was iffy. The execution was stilted. The conducting was awkward. The playing was tentative. The performance was lackluster. The crowd response was muted. The members of the orchestra were disappointed. The Moody Minstrel was out of the building and in his BLUE RAV4 headed homeward as soon as he could get out of there.

At least we had another chance to redeem ourselves on Sunday the 25th. Things got off to an awful start (i.e. no one told me our performance had been rescheduled half an hour earlier, so I showed up late...forcing them to reschedule it again). However, this time the stage was set up properly and the orchestra was able to tune up. I felt much more in the groove with my conducting, and the players responded well. It was a much better performance than Saturday's had been, and the audience response reflected it. We all felt much better afterward.

(When we had returned backstage one of the violinists said, "Now I finally understand these tunes! Can we perform them again?)

I stayed long enough to hear some of the other performances, and then I thought, hey! Since I had gone to so much trouble for an art exhibit, the least I could do was see the exhibit, right? Especially since I had a complimentary ticket! Well, I did just that. I left via the stage entrance, went around to the front of the Culture Hall, and went in to find the usual group manning the reception desk and door stations. (Kashima seems to have its own "inner circle" which is involved with if not in charge of just about every significant event that takes place in the city. I'm well acquainted with most of them.) I also found a LOT of people. I hadn't expected it to be so crowded, but apparently the artist was very popular. When I finally got to the first group of paintings I understood why, too, because I realized with a shot that I had seen them before. In fact, I'd had one of the author's books for nearly a decade!

Tomihiro Hoshino was a young and very active P.E. teacher when he broke his neck demonstrating a double somersault to his students and wound up paralyzed from the neck down. At first depressed and fighting for his life in a hospital, he later came to learn how to write holding a brush in his mouth. A sequence of events led him to develop an increased appreciation for life, nature, and God, and that led him to start painting. The rest is history.

The overwhelming majority of his works are essentially illustrated poems, i.e. the words with an accompanying picture. Most are in an ethereal watercolor, but some are in more vivid media. His poems are generally of a deeply reflective nature, showing clearly his great love of natural beauty, particularly of flowers. Some are of a more psychological and/or philosophical bent. There are also some that reflect his religious beliefs, but always in a subtle rather than "in-your-face" manner, for example:

When I thought life was the most important thing,

Life was naught but misery.

When I realized there was something more important than life,

Life was naught but joy.

(Translation my own.)

One interesting thing about Hoshino's work is that he almost always provides an English translation. Most of his books, including the one I own, are bilingual. Even the art exhibit I visited included a placard with a translation for each individual work. However, I did my best not to look at them. You see, it is easy to translate the meaning of words between languages, but not the nuance. You wind up meaning the same thing but saying something different. Therefore, if you want to grasp the heat of the moment when the author wrote the work, you should read it as he wrote it in his own language.

Besides, even though I hear the translations were all made by native English-speakers, I found the ones I looked at sadly clunky. The writers just translated the Japanese of the poems into English without any consideration for the feeling or the flow. It turned beautiful poetry into very awkward and lifeless prose. Frankly, I don't know why they didn't ask poets to do the transliterations, but that's just my moody minstrel way of thinking. (But if I were asked...)

I found Hoshino's work very moving, and I thoroughly enjoyed the exhibit even with the crowds and the stuffiness. I took my time, reading every single poem and enjoying the pictures that went with them. I also couldn't help but feel a surge of pride knowing that I'd had a part in that exhibit, taking the music for a couple of his poems and making them my own work of art.

Translation:

Translation:The things I can do,

Such insignificant things,

But for them

I am grateful.

If I can do them,

They are much greater things.

- Tomihiro Hoshino

(I won't tell you how much I spent at the gift shop...)

Labels: art, Japan, poetry, Tomihiro Hoshino

5 Comments:

I had a nice response that Blogger unceremoniously eliminated.

Nonetheless, a great experience and I am glad you were able to pull off a good performance considering some of the improbabilities.

PS - Your Hoshino links have an extra http:// at the end which breaks them.

By Don Snabulus, at 5:47 AM

Don Snabulus, at 5:47 AM

Your young musicians seem to be much less disciplined this year. They need something positive to motivate them.

Seems like some of the coordinating staff at the school are also ...

Pull a rabbit out of your hat!

Uhoh, NO HAT!

By Anonymous, at 7:44 AM

Anonymous, at 7:44 AM

Don

Blogger seems to have a thing for that at times.

Thanks for pointing out the link glitch. I think I know what happened, and I have fixed the problem.

Dave

Um, Dave, the musicians in the chamber orchestra were members of the Kashima Philharmonic, i.e. they were all adults. Three of them are professional musicians. At least one other is a music teacher. It's not really a motivation problem. If anything, I think the successes of the last few major performances have made them a bit more smug than they should be.

By The Moody Minstrel, at 1:13 PM

The Moody Minstrel, at 1:13 PM

Adults? Somehow, from their behavior I just assumed...

Yes, smugness and a lack of preperation.

By Anonymous, at 7:45 AM

Anonymous, at 7:45 AM

Talk about translations, we get a lot of weird ones on VCDs and DVDs here. I sometimes think the translation was done without the person watching the movie. Hilarious mistakes.

A most enjoyable post, MM. Thanks. Beautiful painting. Gave yourself an early Father's Day gift, eh? ;)

By HappySurfer, at 3:59 PM

HappySurfer, at 3:59 PM

Post a Comment

<< Home