Life and Death in the Big City, pt. II

As with my mother-in-law, the grandmother who died recently had her funeral scheduled for one week after her death, partly because of limited availability and partly because of Buddhist superstition regarding calendar dates (i.e. there are lucky and unlucky days that follow a regular cycle). Although she is scheduled to be buried in the greater family's graveyard here at our local temple, the action-packed sequence of events that constitute the Japanese funeral was to take place at a funeral home/crematorium there in Tokyo not far from where she lived.

I've described the process involved in the Japanese funeral before (when my MIL died), but I'll briefly reiterate. There are actually three different observances. The first, called tsuya (通夜), is a sort of preliminary rite held the evening before the main service, known as sōgi (葬儀). This is followed immediately by the cremation, after which the family members take turns putting the remaining bone fragments into the burial urn. There are also feasts after the tsuya and again after everything is finished. At any rate, the whole thing takes a couple of days to complete.

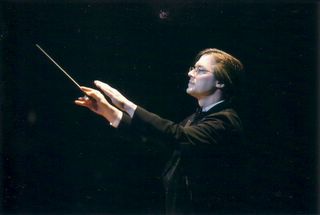

As it happened, the calendar worked out in my favor. The sōgi and cremation were to be on Thursday, which I already had off for my regular substitute Saturday half day and "training day". The tsuya was on the Wednesday before that, which I already had off because the Ye Olde Academy music club was participating in a regional high school music event. I went to that just long enough the direct the performance of the Flying Eggheads jazz band before lunch, and then I took my leave, hurried home, threw on dress black, loaded my wife and son in the BLUE RAV4 (My daughter, as I mentioned in the last post, was away on a school trip), and headed for Tokyo.

Traffic was thankfully light, and with the help of Navi-chan (cute, electronic fanfare), I was able to find our hotel without any trouble. Of course, parking was another story; the family had been booked into a medium-sized travel hotel not so far from the funeral home, but its parking lot was probably designed to humiliate country hicks like us. It consisted of a row of two-level elevator parking spaces arranged around a lane that seemed impossibly narrow even without the obstacles. Having no idea how to operate the elevators (and having NO help from the hotel staff whatsoever), I just tried to back into one of the lower levels...and found out the hard way that my BLUE RAV4 was too tall to fit. (Luckily the thing was cushioned.) Abandoning that idea, I aimed instead for the one lot that was in the lowered position, i.e. open above. Maneuvering my car into the space was an excruciating ordeal of going forward and backward a few centimeters at a time, gradually rotating myself enough to get the wheels into the grooves. Once that was done, I was able to get us checked into the room so we could clean up a bit and then grab a taxi for the funeral home. We got there just in time.

Of course, as with so many things here, "just in time" translated as "hurry up and wait", but it gave us time to greet various relatives we hadn't seen since the last time someone died.

The funeral for my MIL in 2008 was held at a typical funeral home here in the country, and we had it all to ourselves. However, this time the Tokyo-based funeral for my wife's grandmother was in a very Tokyoesque, big complex like a multiplex cinema with several (small) service rooms all crammed in next to each other. We'd brought the priest from our local temple to conduct the rites. As with the overwhelming majority of rural temples, ours is of the Sōtō sect, which is Zen Buddhist. Sōtō rituals tend to be rather low key; the "hocus pocus" is kept to a comfortable minimum led for the most part by the priest, whose chants I've noticed are never exactly the same. This contrasted sharply with the group in the room next to ours. They were obviously of one of the mainly urban Nichiren sects, who are very big on (loud) unison chanting and don't give a damn about any heretics outside their group. All the time our tired, aging priest did his best to lead our simple tsuya ceremony, a blaring cacophony of, "Namu-Myōhō-Renge-Kyō," repeated over and over like a college basketball cheer raged from next door. As if to add insult to injury, the official attendant/hostess of our event apparently wasn't familiar with our country bumpkin Sōtō funeral procedures, and the priest had to pause and gesture for her to carry out the next step. There were some annoyed looks in our group, but we managed to avoid a repeat of the intersect battles that kept trashing parts of Kyoto back in the 13th to 16th centuries.

The feast after the tsuya was, well, a typical greater family feast. I purposefully stuffed myself so that I wouldn't be done in by the constant refilling of my glass by distant relatives of my wife eager to chat with a foreigner (and get him as drunk as possible). I managed to come away in good shape, and we got back to the hotel without incident. Once there, however, my wife and I found out that the drainpipe shared by the sink and shower was not only mismatched but also partly stopped up; using the shower resulted in the bathroom floor becoming a pool. We were too tired to care too much. We turned in early for what promised to be our first good night's sleep in ages. (Or at least it would've been if I hadn't been awakened by horrible heartburn at 3 a.m..)

The next morning we got up, had breakfast, put our dress blacks back on, and caught a taxi for the funeral home again. We'd gotten about halfway there when my son noticed that he'd forgotten the farewell letter he'd written (an important tradition), so we asked the driver to turn around. We finally got to the funeral home just in time for the actual funeral, or sōgi. It was similar to the tsuya the night before (including the loud Nichiren yelling next door), but there were more people there...such as members of my father-in-law's family (including one aunt who recently sued him). (I also couldn't help noticing that there was one large bouquet that had been sent by the relatives on FIL's side who live in Rikusen Takada, Iwate Prefecture, a city completely obliterated by the tsunami last March. They're apparently doing okay even though their neighborhood and main shopping areas are gone.) There were also some more intense farewell gestures and lots more tears shed. Once that was all done, the casket was put in a hearse and driven across the parking lot to the crematorium, where we gave a last prayer, watched as the casket was loaded in the oven, and then waited until it was time to sort out the ashes.

Special chopsticks are used to pick up the remaining bone fragments and put them in the burial urn. It is always done by two individuals in tandem so as to reduce the risk of a curse or possession. Once everyone present has had a turn, the official attendant carefully places the remaining bits in the urn saving the skull fragments for last. Then it's all done till the burial takes place. But of course there is another feast after the rites are done for the day. (I avoided drinking since I had to drive, but I stuffed myself silly...despite being chatted up still more by people eager to compare the Japanese and American educational philosophies.) Then we went back to the hotel, got back into the BLUE RAV4, and headed for home.

Thank heaven there was a Starbucks at the highway rest stop we picked for a break...

I'm told the burial will take place in about two more weeks. It won't be in Tokyo, but will be here at our local temple and graveyard here in Namegata. That'll make it simpler and quieter. It won't be as flashy, and I'm sure there won't be as many people there, but at least we won't have loud, invasive chanting next door or an attendant who doesn't know what to do. I also won't have to worry about not being able to navigate the parking lot.

I've described the process involved in the Japanese funeral before (when my MIL died), but I'll briefly reiterate. There are actually three different observances. The first, called tsuya (通夜), is a sort of preliminary rite held the evening before the main service, known as sōgi (葬儀). This is followed immediately by the cremation, after which the family members take turns putting the remaining bone fragments into the burial urn. There are also feasts after the tsuya and again after everything is finished. At any rate, the whole thing takes a couple of days to complete.

As it happened, the calendar worked out in my favor. The sōgi and cremation were to be on Thursday, which I already had off for my regular substitute Saturday half day and "training day". The tsuya was on the Wednesday before that, which I already had off because the Ye Olde Academy music club was participating in a regional high school music event. I went to that just long enough the direct the performance of the Flying Eggheads jazz band before lunch, and then I took my leave, hurried home, threw on dress black, loaded my wife and son in the BLUE RAV4 (My daughter, as I mentioned in the last post, was away on a school trip), and headed for Tokyo.

Traffic was thankfully light, and with the help of Navi-chan (cute, electronic fanfare), I was able to find our hotel without any trouble. Of course, parking was another story; the family had been booked into a medium-sized travel hotel not so far from the funeral home, but its parking lot was probably designed to humiliate country hicks like us. It consisted of a row of two-level elevator parking spaces arranged around a lane that seemed impossibly narrow even without the obstacles. Having no idea how to operate the elevators (and having NO help from the hotel staff whatsoever), I just tried to back into one of the lower levels...and found out the hard way that my BLUE RAV4 was too tall to fit. (Luckily the thing was cushioned.) Abandoning that idea, I aimed instead for the one lot that was in the lowered position, i.e. open above. Maneuvering my car into the space was an excruciating ordeal of going forward and backward a few centimeters at a time, gradually rotating myself enough to get the wheels into the grooves. Once that was done, I was able to get us checked into the room so we could clean up a bit and then grab a taxi for the funeral home. We got there just in time.

Of course, as with so many things here, "just in time" translated as "hurry up and wait", but it gave us time to greet various relatives we hadn't seen since the last time someone died.

The funeral for my MIL in 2008 was held at a typical funeral home here in the country, and we had it all to ourselves. However, this time the Tokyo-based funeral for my wife's grandmother was in a very Tokyoesque, big complex like a multiplex cinema with several (small) service rooms all crammed in next to each other. We'd brought the priest from our local temple to conduct the rites. As with the overwhelming majority of rural temples, ours is of the Sōtō sect, which is Zen Buddhist. Sōtō rituals tend to be rather low key; the "hocus pocus" is kept to a comfortable minimum led for the most part by the priest, whose chants I've noticed are never exactly the same. This contrasted sharply with the group in the room next to ours. They were obviously of one of the mainly urban Nichiren sects, who are very big on (loud) unison chanting and don't give a damn about any heretics outside their group. All the time our tired, aging priest did his best to lead our simple tsuya ceremony, a blaring cacophony of, "Namu-Myōhō-Renge-Kyō," repeated over and over like a college basketball cheer raged from next door. As if to add insult to injury, the official attendant/hostess of our event apparently wasn't familiar with our country bumpkin Sōtō funeral procedures, and the priest had to pause and gesture for her to carry out the next step. There were some annoyed looks in our group, but we managed to avoid a repeat of the intersect battles that kept trashing parts of Kyoto back in the 13th to 16th centuries.

The feast after the tsuya was, well, a typical greater family feast. I purposefully stuffed myself so that I wouldn't be done in by the constant refilling of my glass by distant relatives of my wife eager to chat with a foreigner (and get him as drunk as possible). I managed to come away in good shape, and we got back to the hotel without incident. Once there, however, my wife and I found out that the drainpipe shared by the sink and shower was not only mismatched but also partly stopped up; using the shower resulted in the bathroom floor becoming a pool. We were too tired to care too much. We turned in early for what promised to be our first good night's sleep in ages. (Or at least it would've been if I hadn't been awakened by horrible heartburn at 3 a.m..)

The next morning we got up, had breakfast, put our dress blacks back on, and caught a taxi for the funeral home again. We'd gotten about halfway there when my son noticed that he'd forgotten the farewell letter he'd written (an important tradition), so we asked the driver to turn around. We finally got to the funeral home just in time for the actual funeral, or sōgi. It was similar to the tsuya the night before (including the loud Nichiren yelling next door), but there were more people there...such as members of my father-in-law's family (including one aunt who recently sued him). (I also couldn't help noticing that there was one large bouquet that had been sent by the relatives on FIL's side who live in Rikusen Takada, Iwate Prefecture, a city completely obliterated by the tsunami last March. They're apparently doing okay even though their neighborhood and main shopping areas are gone.) There were also some more intense farewell gestures and lots more tears shed. Once that was all done, the casket was put in a hearse and driven across the parking lot to the crematorium, where we gave a last prayer, watched as the casket was loaded in the oven, and then waited until it was time to sort out the ashes.

Special chopsticks are used to pick up the remaining bone fragments and put them in the burial urn. It is always done by two individuals in tandem so as to reduce the risk of a curse or possession. Once everyone present has had a turn, the official attendant carefully places the remaining bits in the urn saving the skull fragments for last. Then it's all done till the burial takes place. But of course there is another feast after the rites are done for the day. (I avoided drinking since I had to drive, but I stuffed myself silly...despite being chatted up still more by people eager to compare the Japanese and American educational philosophies.) Then we went back to the hotel, got back into the BLUE RAV4, and headed for home.

Thank heaven there was a Starbucks at the highway rest stop we picked for a break...

I'm told the burial will take place in about two more weeks. It won't be in Tokyo, but will be here at our local temple and graveyard here in Namegata. That'll make it simpler and quieter. It won't be as flashy, and I'm sure there won't be as many people there, but at least we won't have loud, invasive chanting next door or an attendant who doesn't know what to do. I also won't have to worry about not being able to navigate the parking lot.

2 Comments:

When my ex-wife Miho's grandfather died in 2002 we were living in rural Choshi city of Chiba prefecture. I never had to endure a marathon like you went through, in fact, I ended up babysitting my kids while Miho and her family took care of all of the ceremonies. Glad you made it through unscathed, also glad you didn't crumple the roof of your BLUE RAV 4.

By FragBait, at 2:06 PM

FragBait, at 2:06 PM

Andy, how long did you live in Choshi before you headed back stateside?

By The Moody Minstrel, at 6:57 PM

The Moody Minstrel, at 6:57 PM

Post a Comment

<< Home